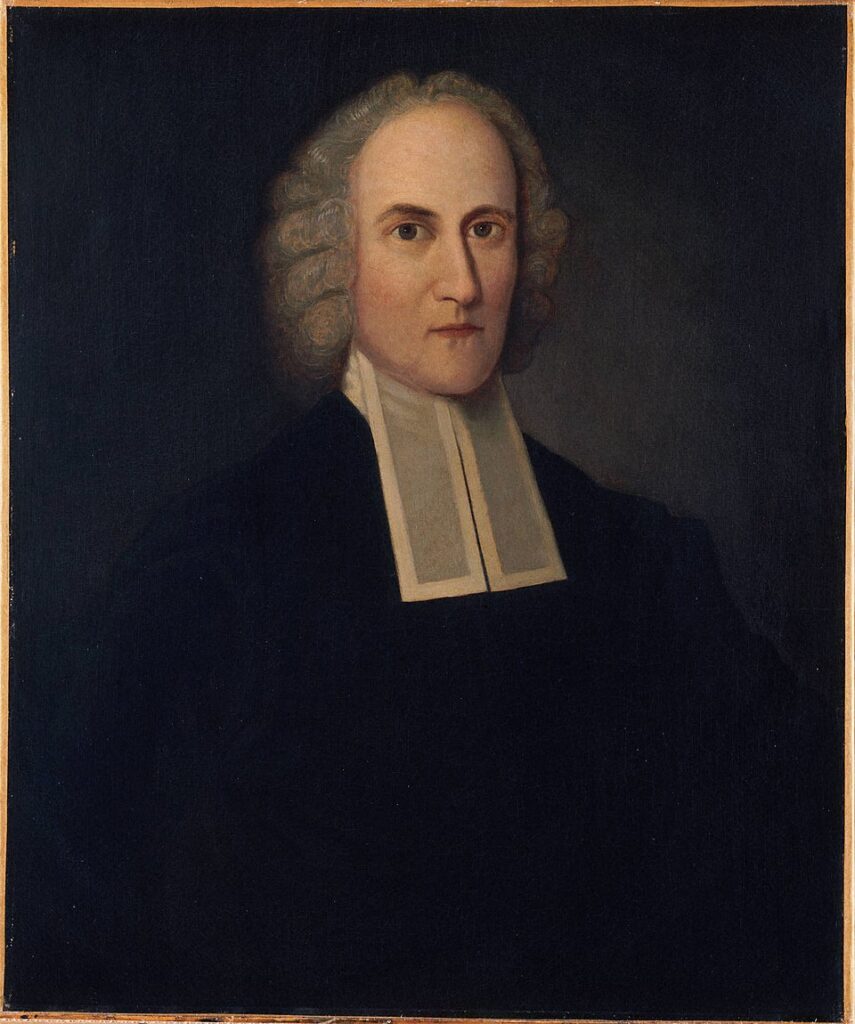

Among the Billions: Jonathan Edwards

Jonathan Edwards: An Ordered Mind

Series Note — Among the Billions

Across billions of human lives, a small number of individuals seem to stand out—not because they were flawless, but because of how they lived and what they chose to do with their time. This series looks closely at those lives as case studies, not legends.

Where He Came From

Jonathan Edwards was born in 1703 in East Windsor, Connecticut, into a household shaped by discipline and learning. His father was a minister and educator; his mother came from a prominent clerical family. Books, sermons, and argument were part of daily life.

Edwards was intellectually precocious. He entered Yale College at just thirteen years old, already fluent in classical learning and logic. While other students struggled through assignments, Edwards absorbed material quickly and began writing private notebooks exploring philosophy, theology, and natural science.

From early on, his mind worked in systems. He wasn’t content with impressions or slogans—he wanted structure, coherence, and internal consistency.

Early Curiosity and Private Writings

As a young man, Edwards kept detailed notebooks—later known as his Miscellanies—where he recorded thousands of reflections. These entries range from metaphysical arguments about free will to observations about spiders, light, and beauty.

One often-overlooked detail is how solitary this work was. Much of Edwards’ thinking happened in isolation, through long walks and sustained writing. He was not charismatic by temperament. He was methodical, inward, and intensely focused.

Even his religious reflections were analytical. Edwards examined his own experiences carefully, suspicious of emotion unless it could be explained and grounded.

Northampton and Public Life

Edwards eventually became pastor of the Congregational church in Northampton, Massachusetts, succeeding his grandfather, Solomon Stoddard—a dominant religious figure in the region.

Northampton was not a quiet backwater. It was a center of religious influence in colonial New England. Edwards’ sermons there, particularly during the 1730s and 1740s, placed him at the center of the First Great Awakening.

Despite later reputation, Edwards’ preaching style was restrained. He read from manuscripts, spoke calmly, and avoided dramatic delivery. The emotional reactions associated with his sermons came from content, not performance.

His most famous sermon, Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, became widely known not because of theatrical delivery, but because of its logical progression and vivid imagery.

A Famous Puritan — and the Last of Them

Edwards is widely regarded by historians as the last great Puritan. By the time he came of age, the original Puritan social experiment was already weakening, challenged by Enlightenment ideas and cultural change.

Rather than abandoning Puritan theology, Edwards refined it. He retained its seriousness about sin, conversion, and divine sovereignty, while engaging contemporary philosophy—particularly John Locke and Isaac Newton.

Historians such as George Marsden and Perry Miller describe Edwards as the intellectual culmination of American Puritanism: not its collapse, but its most sophisticated expression.

Personal Limits and Tensions

Edwards’ intellectual rigor often came at a relational cost.

He struggled to communicate his expectations to ordinary congregants. His sermons were demanding. His moral standards were strict. Over time, tension grew between Edwards and the Northampton church.

Edwards was not politically skilled. He underestimated resistance and overestimated the willingness of his congregation to follow him into tighter discipline.

Controversies and Criticism

Dismissal from Northampton

In 1750, Edwards was dismissed from his pastorate after insisting on stricter requirements for church membership and participation in communion. The congregation voted against him.

The dismissal was public and humiliating. Edwards lost influence, income, and standing almost overnight. For a thinker of his stature, it was a severe professional and personal blow.

Revival and Emotional Excess

Edwards defended the Great Awakening against its critics, but he was also uneasy with its excesses. He criticized emotional displays that lacked moral change, placing him in an uncomfortable middle ground.

Revival opponents accused him of encouraging fanaticism. Revival supporters sometimes found him overly cautious and analytical.

Reputation of Fear-Based Theology

Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God became a lightning rod for criticism. Later readers often reduced Edwards to a single sermon, portraying him as obsessed with fear and judgment.

Modern scholars argue this view distorts his work, but the criticism persists and continues to shape his popular image.

Later Years and Writing

After leaving Northampton, Edwards served as a missionary in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, working among Native Americans. It was a quieter life, removed from influence and controversy.

Ironically, it was during this period of relative obscurity that Edwards produced some of his most important work, including Freedom of the Will and The Nature of True Virtue.

These texts established him as one of the most original philosophers produced in early America.

Historical Significance

Jonathan Edwards stands out not because he was widely liked, but because his thinking endured.

His work shaped American theology, influenced later evangelical movements, and continues to be studied in philosophy, religious studies, and history departments. Unlike many revival-era figures, his reputation grew after his death rather than fading.

He is remembered not for charisma or popularity, but for intellectual seriousness—and for trying to impose order on questions most people leave unresolved.

Takeaway

Edwards is remembered among billions because he thought carefully, wrote relentlessly, and accepted the cost of coherence.

References & Further Reading

Primary Works

- Edwards, Jonathan. Freedom of the Will

- Edwards, Jonathan. Religious Affections

- Edwards, Jonathan. The Nature of True Virtue

Biographical & Scholarly Studies

- Marsden, George. Jonathan Edwards: A Life

- Miller, Perry. Jonathan Edwards

- Yale University, The Works of Jonathan Edwards

Leave a Reply